In the Beginning…

Before the Otter Lake Landfill began operations in 1999, garbage generated by the people and businesses of Halifax was buried at the Highway 101 Landfill (1975-1996). Named for its location across the highway from the communities of Upper, Lower and Middle Sackville, the facility was more commonly known as the Sackville Landfill. It was operated by the Metropolitan Authority, which was established by the City of Halifax, the City of Dartmouth, the Town of Bedford and Halifax County to manage certain issues that spanned the four municipalities that made up the Halifax metropolitan area. These four municipalities were amalgamated in 1996 as one municipal unit, the Halifax Regional Municipality. Amalgamation meant the Metropolitan Authority was no longer needed and it was closed.

Motorists could smell the landfill as they travelled along the adjacent highway. A large seagull population made its home there. Plastic bags hung from surrounding trees, and at times leachate (liquid from inside the landfill) oozed out of the sides of it. Over time, the landfill grew taller than its original design as the municipality received approval to keep it open past its design life by

Leachate was collected on-site, treated and released into the Sackville River, which ran alongside the landfill. As of 2018, 20 years after the landfill was closed, leachate continues to flow out of the landfill, through the leachate treatment facility and into the Sackville River. In 2014, Halifax considered trucking leachate from the new Otter Lake Landfill to the Sackville leachate treatment facility, an idea that was opposed by many local residents.

Currently, methane gas generated by the rotting waste in the landfill is being captured and turned into energy. Halifax Regional Municipality receives $60,000 annually through the sale of the gas.

Community Compensation

The negative impact of the landfill on the neighbouring communities resulted in financial compensation paid by the Metropolitan Authority to affected residents. This compensation took two forms: the municipality offered residents market value for their homes in acknowledgement of the landfill’s impact, and the Community of Sackville Compensation Fund was established to “provide compensation to the Community of Sackville for acting as

As the Sackville Landfill approached its capacity limit, the Metropolitan Authority initiated a process in 1989 to find a new waste disposal solution. In 1991, the Authority chose to pursue waste incineration.

The Incineration Proposal

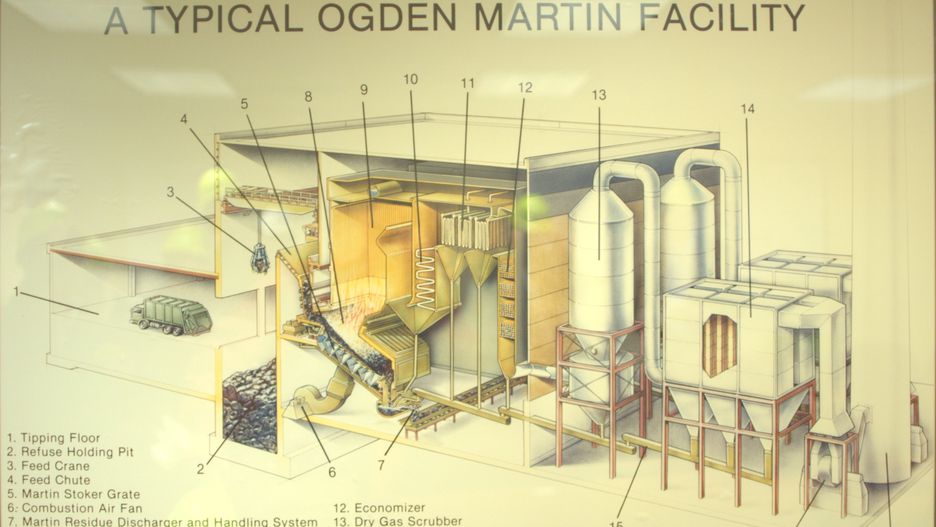

This proved to be a controversial proposal. The Metropolitan Authority staff chose incineration company Ogden Martin to build an incinerator to serve the region for 25 years at a capital cost of $119.8M. The City of Halifax was on the hook for 52 per cent of construction costs based on its share of the population of the region. This was unacceptable to the City of Halifax Council, which voted unanimously against the project. However, the City of Halifax held only three of the 11 Metropolitan Authority seats. The City of Dartmouth and Halifax County each had three seats, and the Town of Bedford had two votes.

When the time came to decide on incineration, a majority of the Metropolitan Authority members approved a vote on the proposal. Members from Dartmouth and the County supported the project and Bedford abstained, leaving only the City of Halifax voting against it. City of Halifax representatives walked out of the meeting and threatened to pull out of the Metropolitan Authority altogether.

The proposal was c

The incineration project was ultimately turned down by the Minister of the Environment on July 15, 1994 after an Environmental Assessment “citing high capital costs, most of which will be spent outside of Nova Scotia and the probability of those costs increasing both during construction and while upgrading to meet newer standards during the lifespan of the incinerator.” The Minister found that there was not enough waste generated by the municipality to make the per-tonne cost of the project reasonable.

The incineration project was abandoned and the search for a new landfill site began.

The County Assumes Responsibility for Finding a Solution

With incineration off the table, Halifax County realized that the disposal solution was going to be a landfill, and it was the only municipality with enough undeveloped land to host it. Realizing the Metropolitan Authority could choose a site they did not like, County representatives sought control over landfill siting and operation. Eventually, the other municipalities agreed, and on September 6, 1994, Halifax County took over responsibility for waste management from the Metropolitan Authority.

Understanding that siting a landfill was going to be

Inviting the Community to Solve the Waste Problem

In voicing their opposition to incineration, many community residents had expressed concern about the lack of recycling and other diversion initiatives proposed by the Metropolitan Authority. Recognizing these concerns, the County decided to undertake a revolutionary approach to waste management, inviting community members to collaborate on the development of a comprehensive waste management strategy that included waste diversion and disposal. They hired a consulting consortium (Vaughan Engineering and Lura Consulting) to facilitate a joint planning exercise for a new waste management system. The consultants had two primary responsibilities. The first was to provide facilitation and support services to a committee of residents to develop a waste management strategy and find a landfill site. The second was to provide engineering and technical support to the committee to assist in developing waste diversion and disposal solutions. This arrangement put the members of the community in charge of developing the solutions, rather than the consultants. This was a unique and innovative approach to planning that many, including other waste management consultants, said was unlikely to succeed.

Minimizing Waste

The Community Stakeholder Committee’s (CSC) priority was waste diversion. Wanting to avoid the same problems encountered with the Sackville Landfill, members decided they could not site the landfill responsibly until they knew what would go in it. If they could keep material out of the landfill that caused odours and attracted vermin and birds, they could design a landfill that would not be a nuisance to neighbours. Risks associated with the landfill had to be understood and mitigated.

CSC members believed the landfill could be made relatively benign through effective recycling and composting programs that diverted problem materials. If these diversion efforts were successful and risks of adverse impacts of the landfill were minimized or eliminated, then perhaps the landfill could be located closer to population centres. This would have environmental advantages. It would not only reduce the distance waste would be transported but also the related use of fossil fuels. Additionally, it would protect wilderness areas by eliminating the construction of a long road into an undeveloped area to keep the landfill far away from people.

The CSC conducted a comprehensive analysis of the waste stream to determine what could be recycled or composted, and how much diversion could be accomplished. After careful consideration, the committee designed a waste management system with a recycling stream that would be expanded beyond the existing program. It also included a brand-new curbside organics collection program meant to divert kitchen scraps, leaves and other yard waste for composting. Although this program was relatively expensive and required construction of facilities and delivery bins for all residents, the committee believed it was important to keep rotting organic waste out of the landfill to avoid the odours, leachate and bird populations that had been common at the Sackville Landfill.

Despite being new for Halifax, this progressive approach to composting had been adopted in other parts of Canada, such as Prince Edward Island and the municipalities of Guelph and Saint Thomas, Ontario. Yet these examples, despite their success, were limited in number, and so it was a bold step for the CSC to include composting in its waste management strategy.

The CSC strategy also included promotion of waste reduction, reuse, user pay and material bans from the landfill. The CSC determined there should be community oversight of the waste management system’s operations and facilities, which led to the founding of the Community Monitoring Committee, which exists today.

On March 25, 1995, the CSC adopted in principle “An Integrated Waste/Resource Management Strategy,” which was later adopted by all four municipalities in the region.

Once all four municipalities were on board, the CSC turned its attention to finding a new landfill site.

Defining the New Landfill

Having determined which materials would not be covered under the increased commitment to recycling and composting, the CSC wanted to ensure they were kept out of the landfill. It recognized that, initially, some people would continue to place recyclables and organics in the garbage and it developed a two-pronged approach to maximize diversion: banning the materials from the landfill and inspecting the waste stream to remove banned materials.

The CSC decided all waste arriving at the landfill would be inspected at a Front-End Processing facility.

Garbage bags would be opened and the contents placed on conveyor belts so that recyclables and organics could be removed by machine and by hand from garbage destined for burial in the landfill.

CSC members determined that the recyclables would be sent to markets to be turned into new products. But the organics presented a bigger problem. It was clear that organic material that had been mixed with garbage would be too dirty to be composted and used as garden soil.

CSC members decided this material would be stabilized in an on-site composting facility and broken down into an inert soil-like substance that could be used at the landfill for landscaping purposes. Even if the composted organic waste was not suitable for landscaping, the raw organic material would not go into the landfill where it would break down and generate methane gas and odours. This would ensure minimal impacts on residents from the landfill, unlike the Sackville Landfill.

Based on that vision, the new landfill facility was defined and sized to serve the community for 25 years. Rather than just being a large hole in the ground filled with garbage, the facility would include a sorting building (known as the Front-End Processing Facility), an organic composting facility (called the Waste Stabilization Facility), and containment liners to enhance environmental and community protection. There was no facility like it anywhere else in the world.

Finally, the landfill would adhere to the standards of a modern second-generation facility, with two containment liners and a leak-detection system, as required by Nova Scotia Environment.

Finding the Landfill Site

After deciding what would go into it, the CSC turned its attention to finding an appropriate site for the landfill. Committee members were confident that the expanded collection and diversion program, coupled with the protections afforded by the Front-End Processing facility (FEP) and the Waste Stabilization Facility (WSF), meant there was little chance the new landfill would have impacts on neighbouring properties as was experienced in Sackville.

When the CSC began considering appropriate sites, it established three sets of criteria:

- Regulatory criteria

- Community criteria

- Opportunity criteria

The regulatory criteria were based on government regulations for the siting of landfill facilities. For example, landfill facilities cannot be established in First Nations communities or near airports (to protect airplanes from birds). There are also distance restrictions related to water bodies. These regulations are nonnegotiable and they informed the site search. This was the traditional site selection method that consulting engineers used at the time. However, the CSC did not stop there; it then addressed opportunity criteria and community criteria, developing considerations that went beyond the traditional landfill siting approach.

The CSC also developed “community criteria” to reduce the impact on residents. One important consideration was the distance of the landfill site from homes. The regulatory criteria stated landfills must have a buffer area of 1 km from occupied dwellings. However, the Community Monitoring Committee members felt there should be extra protection for residents who sourced their drinking water from wells. They established criteria allowing a landfill to be situated 1 km away from buildings that had piped water service, but required a 3 km buffer from homes on groundwater. In this way, members felt they were reducing the possibility of homes being impacted by groundwater contamination if the landfill liners leaked.

CSC members felt strongly that the landfill facility should not unnecessarily impact wilderness area and wildlife, and should be close enough to the community to reduce transportation distance and thus fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. In looking for sites where impacts could be minimized, members considered opportunity criteria, such as placing the landfill near a 100-series highway, which would enable it to use a planned interchange once developed.

After applying the regulatory, community and opportunity criteria, and using computerized mapping, the CMC selected a short list of three potential landfill sites. Following further review, including geotechnical and groundwater studies, a site off Highway 103 across from Beechville, Lakeside and Timberlea was chosen for the new landfill.

Choosing an operator

Halifax County was not interested in operating the landfill itself, preferring to contract that out. At that time, the provincial government was promoting private-public partnerships for investments in infrastructure, and the County sought a similar arrangement for the landfill. Originally, it was thought that the landfill would be a build, own, operate and transfer (BOOT) facility for 25 years. A worldwide request for proposals was issued to identify potential operators. The winning consortium was a newly formed organization, known as the Mirror Nova Scotia, led by a partnership between the local Municipal Group of Companies and the multinational waste management company BFI.

Shortly after the operator was selected, the region’s four municipal units were amalgamated into one – the Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM).

As the Halifax Regional Municipality negotiated a contract with Mirror Nova Scotia, it abandoned the idea of a BOOT approach and decided it would own the landfill and pay for its construction and operation through a more traditional operating contract. Mirror was contracted to build the landfill facility, including the FEP and WSF, and operate it for the next 25 years.

Community Oversight

Residents of the nearby communities of Beechville, Lakeside and Timberlea were concerned about having a landfill in their area. This was understandable, given that many recalled the problems of the Sackville Landfill. No one wanted a similar facility near them.

While CSC members and the Halifax Regional Municipality assured people they would be protected because the new landfill was state-of-the-art, residents were skeptical. Local Councillor Reg Rankin led an initiative to ensure that these communities received covenants ensuring they would not be adversely affected. To safeguard the covenants, Councillor Rankin insisted that there be oversight of the facility’s operation by members of the local

Halifax Waste/Resource Society

Accordingly, the Halifax Waste/Resource Society was registered with the Registry of Joint Stocks with the express purpose of providing oversight of the Halifax waste management system. This oversight included all aspects of waste management, not just the landfill. This wider scope was felt to be necessary as successful diversion of organics and recyclables was vital to mitigating the risk of adverse effects from the landfill. The Halifax Waste/Resource Society continues to monitor the system, and its membership is open to anyone in the Halifax Regional Municipality. Society members elect a board of nine directors at their annual general meeting.

Halifax Regional Municipality entered into a contract with the Halifax Waste/Resource Society to establish the Otter Lake Community Monitoring Committee (CMC).

The Community Monitoring Committee Structure and Mandate

The CMC is defined in the contract between HRM and the Halifax Waste/Resource Society. The contract was developed with the input of three important parties:

- The Halifax Regional Municipality, the owner of the landfill;

- The local community, which hosts the landfill; and

- Nova Scotia Environment, which regulates the landfill.

The CMC comprises 15 members:

- The nine directors of the Halifax Waste/Resource Society, elected by its membership at its Annual General Meeting

- The two members of Halifax Regional Council who represent the districts near the landfill

- Another member of Halifax Regional Council, appointed by Council

- Two members-at-large, appointed by Halifax Regional Council

- The Mayor of the Halifax Regional Council

The CMC has operated since 1999 and has generally maintained strong and respectful working relationships with the Halifax Regional Municipality, which owns the landfill, Mirror Nova Scotia, which operates it, and the Nova Scotia Environment, which regulates it. Any operational issues that arose between 1999 and 2011 were worked out harmoniously between the parties through discussion and agreement. This cooperative relationship delivered on the expectations of residents, ensuring community and environmental protection from the effects of the landfill operation.

During this period, there were no major landfill operational issues that caused concern. There were generally no odour issues, except for a few months in 2011 when there was a delay in the Halifax Regional Municipality’s approval for a plan to close the 5th cell. Apart from this avoidable incident, the landfill operators were able to ensure that there was no significant impact

Waste Management Review

In 2011, the Halifax Regional Municipality undertook a review to identify efficiencies in the waste management system. When Regional Council approved the staff proposal, it instructed the Chief Administration Officer (CAO) to meet with the Otter Lake Community Monitoring Committee as part of the review. Regional Council recognized the importance of the unique and contractual relationship it had with the Otter Lake CMC. At the Council meeting, the CAO asked why he should meet with “a panel of non-experts” and subsequently undertook the review without meeting with the CMC as instructed.

This was not well-received by the CMC or by members of the local community. It unnecessarily raised fears that the Municipality might not keep promises it had made when selecting the landfill site.

Those concerns were justified in 2013 when the Municipality published the waste management review study by the engineering consulting firm Stantec. In it, the consultants recommended substantial changes to the landfill operation, including:

- closure of the Front-End Processing Facility and the Waste Stabilization Facility;

- elimination of one of the protective layers in the landfill;

- an increase in the height of the landfill above the approved design constraints;

- an increase in the 25-year operational term of the landfill (in keeping with the increased height); and,

- the establishment of other waste management facilities at Otter Lake in a waste management campus, including outdoor curing of compost.

When HRM staff presented the report and its recommendations to HRM Council, some members of Council expressed concern that the CAO had not followed their instruction to meet with the Community Monitoring Committee. Council passed another resolution instructing the CAO to meet with the CMC, but he did not.

As a result, fifteen years of goodwill between the Halifax Regional Municipality and the Community Monitoring Committee was undermined. The CMC became deeply concerned that HRM could unilaterally remove the protections and covenants that had been guaranteed to the affected communities when the landfill was established. It appeared that the Municipality might renege on its promises just to save money.

Community Consultation on Recommended Landfill Operational Changes

As feared, HRM staff drafted recommendations to make substantial changes to the landfill as had been recommended in the report from Stantec. The proposed changes were so drastic that HRM Council required staff to undertake a city-wide consultation on the recommendations. National Public Relations was contracted to undertake the consultations at a cost of approximately $450,000.

During the consultations, which included eight public open houses and online consultation, residents were very clear that they expected HRM to keep its commitments to the local community. When National delivered its December 5, 2013 report, it stated there was not strong support among residents for the landfill changes proposed by staff. The following is quoted from the section on proposed changes.

“Outcomes most important to residents:

“Outcomes most important to residents:

- Honour the contract

- Keep the front end processor and waste stabilization facility

- No reduction of landfill lineR

- No increase in cell height

- No waste campus

- Site a new landfill

• Protect the environment

• Citizen led process

- Shared understanding (HRM/community) of the agreement”

Despite these findings, HRM staff pressed on with the recommendations for changes to the landfill.

Final Recommendations and Council Decision

On January 14, 2014, HRM Council’s Committee of the Whole considered a report from staff with nine recommendations for changes to the waste management system. Recommendations seven through nine dealt with changes to the landfill and included:

- removal of flow control from the Solid Waste By-law, allowing Industrial, Commercial and Institutional (ICI) waste to be exported to landfills outside of the community;

- moving forward to develop plans to make changes to the Otter Lake landfill, including the closure of the FEP and WSF; and

- moving forward to increase the height of the landfill by 15 metres and extend the life of the landfill beyond 2024 (despite the original plan’s 25-year lifespan).

These motions were deferred for discussion at the Environment and Sustainability Standing Committee as they had significant cost and community impact implications.

On December 8, 2015 Regional Council passed a motion to rescind its plan to increase the height of the landfill. Two reasons were cited for this change: the site design had a much larger capacity than staff had expected and allowing the ICI waste to be exported meant that there was more capacity available for residential waste.

Council also voted to defer any further consideration of changes to the operation of the FEP, WSF and any new facilities until 2019.

On May 13, 2016, the Nova Scotia Legislature unanimously passed Bill 176, titled An Act to Maintain the Current Footprint and Certain Requirements of the Otter Lake Landfill. Introduced by local MLA Iain Rankin, the Act ensured that the landfill height could not be increased and that the footprint could not be expanded beyond the original design.

Other Facilities

As stated above, in addition to a landfill, the new waste management system also required composting facilities to handle the organic waste that was to be collected curbside from residences. As well, because organic material was banned from disposal, there was a requirement for composting capacity to handle organics generated by the Industrial, Commercial and Institutional (ICI) sector as well.

HRM issued tenders for two composting facilities capable of processing 25,000 tonnes each per year to handle both residential and ICI organics. It was decided that two facilities would be better than one, providing some redundancy in case one facility had to close for any reason.

After the tendering process was complete, two operators were chosen to build composting facilities, one on each side of Halifax Harbour. New Era Farms was selected to build a facility in the Ragged Lake Industrial Park on the west side of the harbour and Miller Waste was chosen to build a facility at the Burnside Industrial Park. Each facility was expected to operate for 20 years, at which time they could be transferred to the Halifax Regional Municipality.

The composting facilities began operation in 1999 and reached capacity in 2015, requiring HRM to look for a new, larger composting operation with a capacity of 60,000 to 75,000 tons per year to be operated under contract for the next 25 to 35 years.

Although the new waste diversion system also expanded the curbside recycling program to include a larger selection of materials, the existing Material Recycling Facility (MRF) was able to handle the increased tonnage generated without requiring more capacity at the time. The MRF did not require an expansion of capacity until 2018.

The Otter Lake CMC does not have monitoring responsibilities for the recycling and composting facilities. However, the CMC remains interested in them as they are critical to the diversion of waste from the landfill facility.

To Be Continued…

The Otter Lake Facility is expected to be operational until approximately 2070, given current waste generation. The Otter Lake Community Monitoring Committee will continue to monitor the landfill on behalf of nearby residents past the eventual closure of the facility.